Israel has been rocked for several weeks by a heated debate about the future of its judiciary. The present government – the first one in four years to enjoy a clear cut majority at the Knesset, Israel’s parliament – has submitted a bill, as per its democratic prerogative, to achieve a new balance between the Legislative and Executive branches of government, on the one hand, and the Judiciary branch, including the Supreme Court, on the other. This move has been hyperbolically denounced by the opposition and large parts of the media or the public as a “judicial coup”. A more sober approach may be needed here, whatever views or reservations one is allowed to entertain about the reform bill technicalities or the way it has been drafted. Likewise, some comparisons with the French judiciary may be quite useful.

Israel has been a fully democratic State, just like France and the Western countries, since its very creation in 1948. Government in Israel has always been based on elections, even in a context of war or international tension. Israeli citizens have always enjoyed equal rights, irrespective of religion, race or gender. The Israeli media have always been free. It can even be argued that Israel’s democracy predated independence. All kinds of democratic and representative institutions, modelled after Western democratic practice, preceded the State, reaching back to beginning of the Zionist movement over 120 years ago.

However, over the past three decades – since 1992 – democratic normalcy has come under severe challenge, due to a high-handed overreach on the part of the Supreme Court and, as a result, a politicization of the entire judicial branch. This bizarre development was acknowledged by many legal experts, from the conservative Right to the liberal Left, long before the present government was formed. Netta Barak-Koren, a Professor of Law at the Hebrew University in Jerusalem, and a critic of most the reforms envisioned by the present bill, expressed the view that : “The High Court of Justice, and the government legal counsel apparatus in its wake, expanded its sphere of involvement to include political issues, arrogated the authority to determine the contents of basic constitutional principles, based its judicial review (…) on vague value-based tests whose application is unconvincing, strayed from the professional and judicial expertise of the judicial system, and placed the State authorities in a state of constant uncertainty about the validity of their decisions”.

It may safely be argued in this light that bringing the Israeli judiciary system more in line with democratic norms worldwide and restoring balance to the branches of Israel’s government, as it used to be the case until the 1990’s, was overdue.

In 1948, Israel adopted the British Westminster model of government, in which the parliament reigned supreme. The fact that Israel had postponed the promulgation of a comprehensive written constitutional document did not matter. The United Kingdom has developed into a model democracy without such a document. And so had France’s first genuinely democratic government, the Third Republic, from 1870 to 1940.

The classic Israeli parliamentary system held until 1992, when the Knesset passed the Human Dignity and Liberty: Basic Law, during the term of a lame duck government, with only a minority of its members voting. The protocols and statements of the Knesset members and leading jurists of the time demonstrate a lack of intent, and even active opposition, to granting the Supreme Court the power of judicial review.

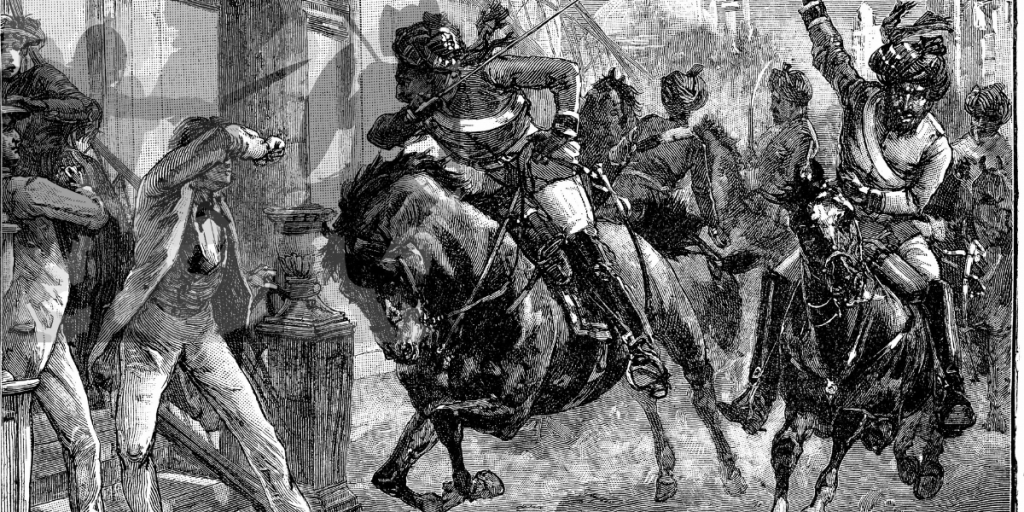

Like Napoleon grabbing the crown from the pope’s hands and placing it on his own head, the Supreme Court, under the leadership of its then president, Aharon Barak, seized the opportunity to launch a self-proclaimed “Constitutional Revolution”, by which the Court empowered itself to strike down laws or alternatively to turn ordinary laws into constitutional laws, and more generally to intervene in the day to day workings of the elected government. Israel is the only country in the world whose judicial system has stealthily and steadily taken over constituent, legislative and executive powers. One explanation for this subversion is that the public was growing impatient with an hyperdemocratic electoral law based on near absolute proportional representation, and the Régime d’Assemblée, reminiscent of the French Fourth Republic, that it implied. Many citizens were convinced at the time that empowering the judiciary as a countervailing power was a feasible solution.

The Judiciary Revolution shortcomings are now to glaring to be ignored. Whereas the French Constitutional Council’s powers of judicial review are quite limited, the Supreme Court’s purview knows no bounds. Unlike the Question Prioritaire de Constitutionalité in which parties must demonstrate a direct violation of constitutional rights, the Supreme Court has opened the door to NGOs and various ‘public petitioners’ to question any laws and policies. The Court regularly interferes in issues of security, immigration, economy and foreign affairs. Based on ambiguous and undefined standards of “reasonableness” – in fact, more often than not, conformity to an ever radicalizing liberal agenda -, the Supreme Court has ordered ministers fired, and demanded that the democratically elected Prime Minister justify his premiership. Recently, the Court has taken to flirting with the idea that it may strike down Basic Laws themselves, despite supposedly being the very basis for its power of judicial review.

Moreover, Israel’s Supreme Court judges are appointed by a committee of nine members dominated by the legal Establishment: while four members are elected officials, three are Supreme Court judges and two members of the Bar Association. This means essentially that the judicial Establishment, as a class, has a veto over judicial appointments, and that a situation is created by which a homogenous, endogamous, self-perpetuating Supreme Court is drawing judges from its own social milieu and ideological background. No other democratic country has descended into such distortions. On the contrary, direct appointment of judges by elected officials is the norm in democracies worldwide, and has not impaired the judges’ independence. In France, for instance, the members of the Constitutional Council are appointed by the presidents of the Republic, of the National Assembly and of the Senate, respectively, with the parliament’s approval. Former presidents of the Republic also sit on the Council.

There are many other outlandish sides to the present judiciary situation in Israel, like the fact that no full or qualified quorum of judges is required at the Supreme Court, and that major decisions are thus being taken by a tiny minority within the Court. Or that, based on a 1993 Supreme Court ruling, the counsel of the Government’s legal advisors nominated by the judiciary Establishment is binding. This can create an absurd situation by which legal advisors, whose task was meant to advise, are empowered to dictate policies to the elected government.

Observers from distant planets will certainly wonder why a much needed reorganization of Israel’s judiciary elicited so much protest and near-hysterical turmoil, instead of being discussed and possibly corrected in an orderly manner. Indeed, more factors have been at work, including latent social, cultural and religious quarrels, or sheer political maneuvering. However, one may also wonder whether Israel’s crisis should not be seen as part of a more general crisis in the Western democratic world. Some parallels are to be drawn between the Benjamin Netanyahu government’s reform-related difficulties and the quasi-insurrection that President Emmanuel Macron is facing if he is to implement his own reform of the retirement system.