Turkey announced a sweeping freeze on trade with Israel last month, due to the war in Gaza. Industrial actors and government officials struggled to understand the in-depth implications of this move, fearing a rise in the prices of many products.

How dependent is Israel on Turkey; which products will be most affected; and how can regulatory steps, of all things, help in at least partially facing the challenge?

Turkey is an attractive destination for Israeli importers due to its geographical proximity, low production costs, and a trade deal dating back to the nineties. Nonetheless, importation from Turkey represents only 5% of all Israeli importation and stood at an average of approximately 4.5 billion dollars annually in the past five years. Importation from Turkey is varied and includes raw materials such as iron and steel (600 million dollars worth in 2023), cement (290 million), paper and cardboard (150 million), and more, as well as consumer products, some of them manufactured in Turkey by international corporations such as cars (315 million) and clothing (230 million), and some from its local market like fruits and vegetables (80 million).

Israel imports some specific products at a higher rate from Turkey than other countries. These are primarily cement (73%) and marble (55%) but there are many other products with rates in the double-digit percentages, such as plastic products, copper and copperware, glass and glassware, paper and cardboard, and more, triggering the concern that prices will rise due to the halt in trade.

Although explicit Turkish support of Hamas should come as no surprise considering Erdogan’s statements and the hosting of senior members of the terrorist organization, the trade restrictions imposed on Israel were sudden and they were implemented immediately. Some importers have already begun to work on solutions, such as finding ways to circumvent the prohibition or importing from other countries. However, aside from the possible effect on prices, importers will also need to undergo regulatory procedures such as obtaining approvals and licenses, meeting different requirements for alternative products, replacing labels and markings, and in general, spending time on learning the procedures and requirements for the new situation.

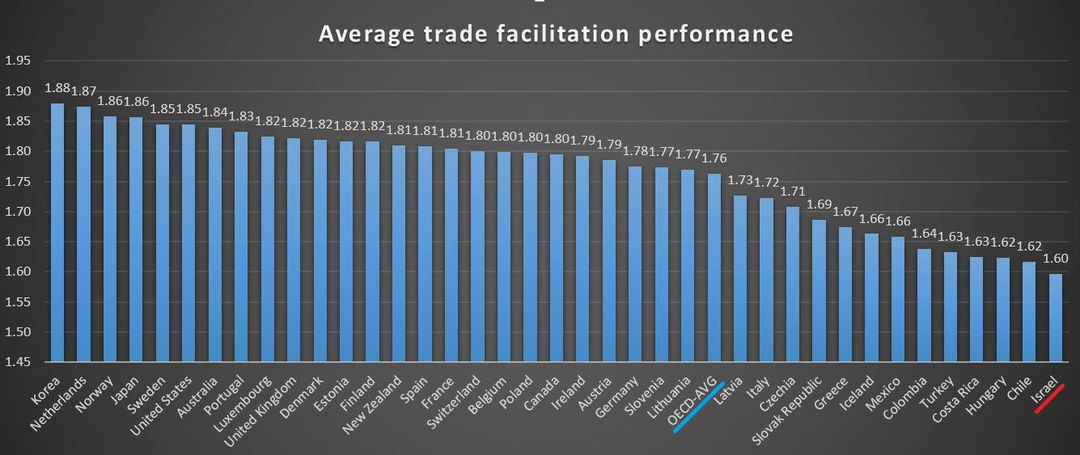

Therefore, aside from the steps Israel should take at the diplomatic level, this is another opportunity to understand the importance of working towards easing the regulatory burden on importation and making it more accessible andtransparent. According to research by the UN Trade and Development Conference, non-tariff trade barriers contribute more than twice to blocking the entry to market than tariff measures. Israel today is rated last among all OECD countries on a measure of ease of trade (measured by Trade Facilitation Indicators or TFIs), even lower than the only member states defined by the World Bank as middle-income – Costa Rica, Colombia, and Mexico. TFIs cover the entire spectrum of trade border procedures such as preliminary requirements, fees, cooperation between different agencies, and more. Another interesting fact to note is that Israel also scores lowest on the good governance and impartiality indicator, a measure that examines transparency, public accessibility, and the impartiality of the agencies involved in importation.

Israel can act in a number of ways to increase transparency and public accessibility. The more it does so, the easier it will be to import and the less we will be dependent on any specific country for goods.

The first step is to transfer to licensing based on a single window and declarations: developed countries are now promoting the “single window” paradigm, meaning, organizing a single system that dispenses information and processes all requests to import so that importers deal with a single regulator rather than with tens of different agencies. All systems but the MASLUL system (the Status System for Licenses and Approvals for Importers) should be abolished, making it the central interface for filing all import requests. This interface should grant automatic importation licenses, as is the practice in the European Common Market.

The second step involves reasoning and grounds for rejection: under the current regulatory regime, government ministry offices can reject requests to import with no explanation. Instead, the requirement to stipulate the reasoning behind decisions to reject untrustworthy importers should be implemented.

Thirdly, service call centers should be established: since it is particularly important to get a reply to license requests within a limited timeframe, service call centers can provide answers to importers’ questions and register reports of ministerial disregard of the directives regarding licensing or excessive waiting times. This will increase transparency and accelerate importation procedures.

Aside from these steps to further accessibility and transparency, the government is currently promoting a reform dubbed “what’s good for Europe is good for Israel”, in an attempt to ease the regulation on importation. For it to succeed and not fall through like previous reforms did, unique Israeli standards must be completely abolished, allowing instead for the free entry of all goods that conform to EU standards.

First published in Arutz Sheva (Israel National News) (“Turkish Trade Embargo: What does it mean for Israel?”, Jun 23, 2024)